By Alex Robinson

The landscape of Rushton’s Liverpool was permeated by slavery and the slave trade: the impact of the slave trade was visible – you may even say inescapable: Mary Ann Galton, daughter of the Birmingham gun manufacturer Samuel Galton, describes St Georges Dock:

“Her groves of masts, the noble estuary…her broad quays covered with

foreign and especially West Indian produce, and the palace-like residences of her merchants.[…] My father had a very large acquaintance with the affluent West India merchants of Liverpool, their houses were like palaces. But what surprised me most …was the multitude of black servants, almost all of whom had originally been slaves.”

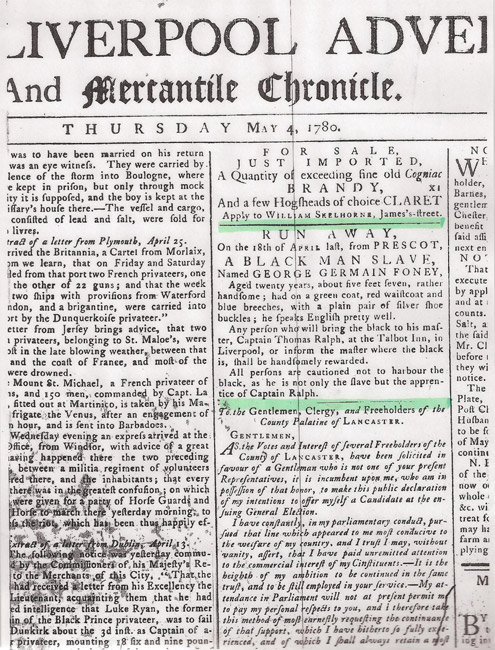

Local newspaper adverts also reveal the slave trade was entirely embedded in the town’s business. This merchant includes an enslaved African boy as one of the commodities he had for sale:

“To be sold 10 pipes of raisin wine, a parcel of bottled cyder, and a negro boy, apply to Joseph Daltera, merchant, in Union Street, who sells at his warehouse near the Salt House, Dock Gates, fine, second, and coarse flour.”

And adverts for runaway slaves demonstrate that enslaved Africans were part of the Liverpool scene, although there was a free Africans presence in the town. The advert below gives a detailed description of the runaway, to distinguish him from the population of free Africans.

But less visibly and more deeply embedded was the impact of slavery on public architecture – some of it financed by the Common Council – such as public walks, crescents, squares and leisure gardens, others by public subscription – churches, schools, theatres, the music hall, the first gentlemen’s library, the lyceum – they were all endowed by the merchant community within which the names of slave traders were prominent. Bryan Blundell who founded the Bluecoat was the first of many slavers not only to salve their consciences but also to gain esteem by philanthropic acts. The Liverpool Infirmary is a case in point, set up in 1749; 7 of the 11 trustees were slave traders.

The slave trade allowed 101 and more Liverpool slavers and their families the leisure to pursue gentility and sensibility and accrue the trappings of a merchant gentleman and to be remembered as the great and the good, whose names were celebrated in the street names which marked their part in the city’s growth and shaped its future. It was the slavers who led the move to build in the outskirts of the town to Everton, Allerton, Walton, West Derby, Wavertree, Allerton, Aigburth, to the Wirral and on into Cheshire.

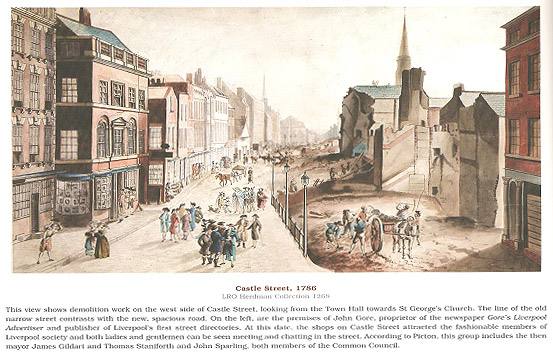

The Common Council itself was dominated by slave traders – 37/41 members were slave traders in 1787 and the leading slave traders were also the mayors of the town – all 20 mayors from 1787 to 1807 were slave traders. A large proportion of the finance deployed by the Common Council originated in the profits of the slave trade and the slave produced goods, and the customs raised on them which grew exponentially in the last quarter of the 18th Century.

The fruit of their efforts was praised fifty years later “there is no town in the Kingdom in which there are so many temples dedicated to the improvement of mankind as in Liverpool, nor can any city provide equal evidence of the zeal of its Merchant Princes in raising mansions for the development of civilisation.” (History of Adult Education, 1851)

It was this slave trading elite who decided how the finance should be deployed as exemplified in these Herdman paintings of the widening of Castle Street in 1787, which identifies the councillors/slave traders Gildart, Staniforth and Sparling in the foreground of the picture.

They, if you like, had the vision for Liverpool’s future which would make Castle Street “[…]Castle Street is to Liverpool what Cornhill is to the City of London, Market Street to Manchester, Princes Street to Edinburgh, the Corso to Rome, the Strada di Toledo to Naples – the embodiment of its character, the centre of its system[…]” (Picton, J A Memorials of Liverpool, 1875).

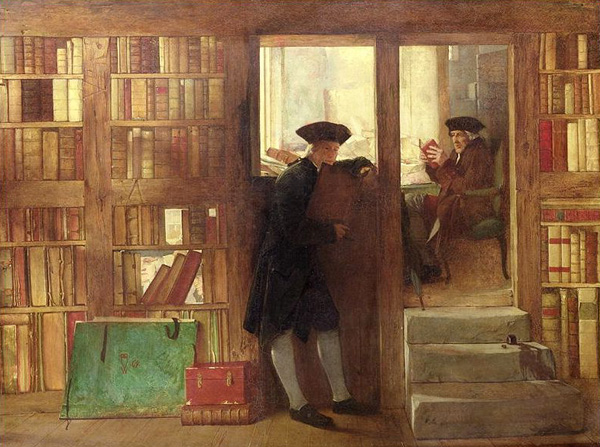

One street away from Castle Street, on Paradise Street, Edward Rushton’s bookshop was at the heart of the European capital of the slave trade. His near neighbour, Reverend John Yates at the Paradise Street Unitarian Chapel was the only minister in the town to denounce the slave trade from the pulpit. Abolitionists lived cheek by jowl with the merchants and ships’ captains who were by the last quarter of the 18th century enjoying a bonanza on the proceeds of the slave trade. Liverpool was vilified by contemporaries for its involvement in the slave trade and its campaign against abolition but there was a handful of well-known antislavery campaigners led, in the public imagination, by William Roscoe, supported by James Currie and William Rathbone but there were others who played an important role – Edward Rushton, Hugh Mulligan, Dr Jonathan Binns, Daniel Daulby, William Wallace, Rev. John Yates, William Rathbone IV and Henry Dannett were all either subscribers to the London based Society for Abolition or writers of tracts and pamphlets supporting it in the early phase 1787-1792 .

To stand up for Abolition in Liverpool was a brave act and there is evidence that those that did suffered for it – the visiting abolitionist Thomas Clarkson was almost forced into the dock when he came to Liverpool in 1787, Dr Jonathan Binns, a Quaker subscriber to the Abolition Committee, left town after an attempt on his life, Rushton was shot at, the bullet narrowly missing his eye, while Roscoe met with violence on several occasions notably after the Abolition of the Slave Trade was passed in Parliament in 1807. The atmosphere was oppressive for any who chose to speak out against the slave trade in Liverpool.