Written by John Graham Davies

Slavery Abolition

Rushton participated in the small anti-slavery movement in Liverpool as his writing and biography show, but on its radical end. Nationally it contained varying opinions, ranging from those who wanted only (or initially) to improve conditions on slave ships and plantations, to those who wanted an end to the trade (whilst allowing existing slaves to continue in servitude), to those who wanted immediate, full emancipation. Judging from his writings, Rushton belonged to the small group arguing for immediate and radical change. His first anti-slavery poem, the West Indian Eclogues, was too radical for most abolitionists because he gave voice to the enslaved, planning revolt rather than meekly petitioning for freedom.

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson, the guiding force of the London Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, visited Liverpool, collecting evidence to put before Parliament. Although Rushton had not been at sea for over 15 years, it was via Rushton that Clarkson was able to interview those sailors brave enough to testify. This would have been dangerous for them both, and Clarkson describes an attempt by a crowd to drown him in Liverpool dock.

The American Revolution

Rushton came to see the battle to free the colonies from the British crown as entirely positive. The writings of men like Tom Paine and George Washington struck a strong republican chord in him, and he wrote a number of poems welcoming the newly independent state. Rushton saw this battle as one of a number of battles for Freedom, and against autocracy, and as an example to others.

Rushton’s letter to George Washington

Rushton was an admirer of Washington, but criticised the political settlement in America for its failure to extend freedom to the enslaved. When he heard later that the first American president had continued to be an owner of slaves, Rushton turned on him. In a passionate letter he lambasted Washington, personally as the owner of slaves, and in his public role for failing to grant them their liberty.

“The man who can boast of his own rights, yet hold two or three hundred of his fellow beings in slavery, would not hesitate […] to employ the most sanguinary means in his power, rather than forego that which the truly republican laws of the country are pleased to call his property. Shame! Shame! That man should be deemed the property of man, or that the name of Washington should be found among the list of such proprietors.”

Although hand delivered by a friend of Rushton’s, the letter was returned to Liverpool, apparently unopened. Did the former president take the trouble to return an obscure, unopened letter, or was he offended by its contents?

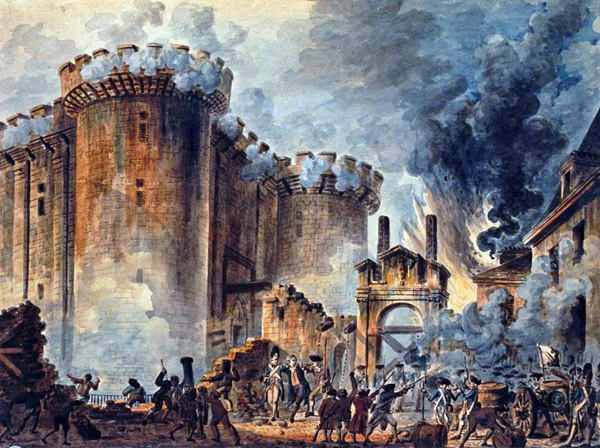

The French Revolution

As with the American revolution, Rushton was strongly attracted to the democratic content of the French revolution, and to its republicanism. His vocal support for the revolution in France continued as late as 1794, even after the execution of the French king and queen:

“Thy real friends, O Liberty!

Must gaze on France with ecstacy,

Must venerate the wondrous deed

Which millions from their shackles freed –

Which shews the anointed things,

How puny, when oppos’d, are kings.”

(from Lines Written After the Birmingham Riots)

Rushton’s stance was well known and made him unpopular, particularly during the early years of the war against France. His tavern and then his bookshop, known as a meeting place for radicals, suffered for years as a result, and he was shot at. Edward’s son described the incident:

He became a noted character, was marked, and by some illiberal villain shot at; the lead passed very close to his eye-brow, but did not do him the smallest injury.

When Robert Southey, the new Poet Laureate and former radical, wrote Carmen Triumphale asserting God’s blessing for Pitt’s war, Rushton’s riposte was sharp and categorical:

“I grieve when earth is drenched with gore,

And realms with woe are covered o’er;

I grieve, and reprobate the plan

Of thanking God for slaughter’d man.”

This fine poem, full of satirical wit and invective, was one of Rushton’s last and reflects the confidence of a man who had weathered the political storm.

The Pressgang

In writings such as Will Clewline, Rushton expressed anger at the arbitrary way in which the Admiralty was able to kidnap and pressgang young men into service on warships. The navy was the largest employer in England, and one out of every three men ‘impressed’ in this way never returned, dying either in war or as a result of the savage regime existing in Britain’s navy at the time.

Rushton’s first enterprise, a tavern, suffered a boycott organised by the Admiralty because Rushton was campaigning against the pressgang, and it went bust. His next venture, as joint-proprietor of the journal, The Liverpool and Lancashire Weekly Herald, suffered the same fate. A Rushton broadside in response to a violent impressment on Liverpool docks was met with an Admiralty demand for a retraction. With his nervous partner minded to print the required retraction, Rushton gave up the paper rather than compromise.

“Ye statesmen who manage this cold-blooded land,

And who boast of your seamen’s exploits,

Ah think how your death-dealing bulwarks are mann’d,

And learn to respect human rights.”

(from Will Clewline)

Combination and Constitutional Reform

In Rushton’s bookshop petitions were signed against slavery, and in favour of reform. Demands included an expansion of the tiny voting franchise and abolition of corrupt constituencies (the ‘rotten boroughs’). During the last five years of the eighteenth century, with the war against Napoleon losing its patriotic sheen, there was a struggle to defend freedom of speech as Pitt introduced bills to ban meetings. The beginnings of trade unionism – then called combination – involved a risky campaign of workers secretly combining together to defend themselves. The Seditious Practices and Meetings Acts, and the Combination Acts attempted to stifle this reform movement.

One of those involved in the London Corresponding Society, the proto-socialist organisation campaigning for reform and for Combination, was John Binns. Binns escaped to the USA after his trial for sedition, and when he passed through Liverpool on his way he visited Rushton’s bookshop and spent the evening with him.

Disability Rights

Once he became involved with the small, Friends of Freedom circle in Liverpool, Rushton made a proposal for regular financial support for blind people from those who could afford it. The idea was developed, initially into a music school for blind people, and then to a fully fledged school. The original premises were two cottages, bought by Rushton himself, and then extended to a purpose built building in 1800.

Women

Rushton wrote a number of ballads, such as The Maniac and Mary’s Death, describing the violence meted out to Irish women at the hands of English soldiers. The use of rape as a tactic of war features in Mary-le-More:

“From her father’s pale cheek, which her lap had supported,

To an out-house these ruffians the lovely girl bore,

With her prayers, her entreaties, her sorrows, they sported,

And ruin’d, by force, the sweet Mary le More.”

These ballads have a firm place in Irish song. Powerful female characters appear in them, and – like other categories of the powerless in other poems – are made to speak. In Mary Le More it is the Irish theme that prevails, and Mary is both the metaphorical embodiment of the violated nation, and a violated woman. Recent research has revealed that the Mary Le More ballad sequence was sung by the United Irishmen during their uprising of 1797.